On Ancient Gods and Present Faith

Exploring Religion + Power: Then and Now

DISCLAIMER Travel is not only about perfect pictures or Instagram-worthy moments. It’s about stepping into other people’s worlds - learning their stories, exploring the threads that run from history into the present, and gaining a deeper understanding of human complexities. I share these thoughts from a place of open inquiry. These places have so much to teach us—lessons that go far beyond being awed by the view. Let’s go!

It was my first morning in Cairo, and already the city pulsed with that dizzying, layered energy only ancient capitals seem to perfect. We moved through streets teeming with movement and sound—car horns and stray dogs, crumbling buildings and flashes of color, the overlapping calls to prayer echoing across rooftops. I’d imagined something more cosmopolitan, but instead found a raw, complicated aliveness. As we headed out on our first day of touring, I had the sense that while the past in Egypt stood eternal—monumental—the present felt tired, stretched thin, and in need of care.

In the distance, the Great Pyramids of Giza shimmered like a mirage—so familiar from history books that they almost felt fictional until we were standing in their shadow. Ancient ruins rose from the desert haze, timeless and massive. They weren’t just architectural feats; they radiated presence. These were monuments not only to lives once lived, but to lives imagined far beyond death. Tourists surrounded the base, led by guides holding flags and hawkers sold their wares at every turn.

Our guide led us through nearby temples, sharing how the pharaohs declared themselves chosen by the gods—divine rulers destined for eternity. But declaring wasn’t enough. Power needed to be seen and believed. And belief, once sparked, had to be sustained. So they built their divinity. They carved stories in hieroglyphs—battles won, blessings bestowed, cosmic alignments confirming their right to rule. They erected statues taller than trees and pyramids aligned with the stars. They filled temples with depictions of themselves as nourished by gods, protected by gods, loved by gods. The symbolism was loud and deliberate. To challenge them was to challenge divinity itself. “This,” our guide said, gesturing to the stone walls around us, “is how you turn power into permanence.”

Echoes of Ancient Gods

That sense of wonder and complexity stayed with me as we traveled south, from Cairo to Luxor to Aswan. We visited sacred sites, ancient quarries, and tombs carved into stone. We stood beneath ceilings painted like the stars, walked the same dusty corridors priests once followed, and peered into burial chambers built for eternity. We entered temple sanctuaries—moving inward from open courts through narrowing rooms, until we reached the heart, the space where gods once resided.

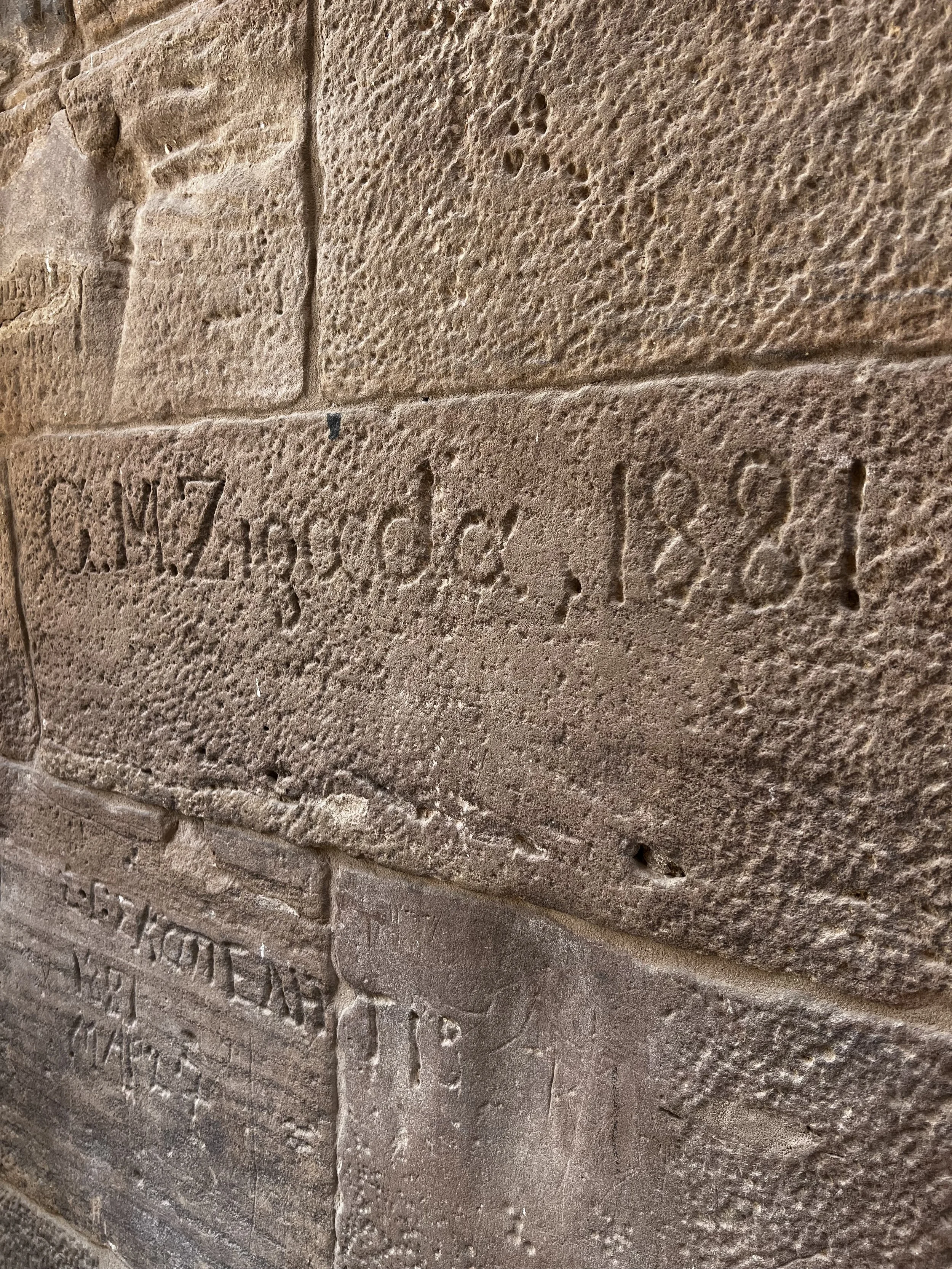

We saw mummified pharaohs, gem-studded furniture, coffins and statues. And etched over all of it were the markings of time—not just the ancient carvings, but later graffiti in Greek, French, English. Names and dates chiseled into permanence: I was here.

Even those who came to conquer or catalog understood that these places demanded to be remembered.

The Echo That Caught Me

But amid the awe and reverence, something else began to surface—a pattern I hadn’t expected, and one I couldn’t ignore. At nearly every stop, our Egyptian guides—each deeply rooted in their own faith—repeated the same idea when speaking about the ancient religion.

“They used religion to control people,” one said as we passed a line of toppled statues. “It wasn’t really about belief. It was about keeping society in order.”

Another pointed out the secret chambers in temples, where priests would speak through cracks in the walls to simulate divine voices. In Kom Ombo, a healing temple, we were told that opium-laced incense created a trance-like haze, helping worshippers feel closer to the gods. “People believed what they were told,” the guide added, half-laughing. “They didn’t know better.” A third guide described the way rulers and priests collaborated to design festivals and rituals that reinforced royal authority, turning myth into law. “Everything had a reason,” she said. “Even the gods served the politics.”

What struck me wasn’t the insight—it was the irony. Each of these guides was devout. One was Coptic Christian fasting for Lent. Another, a Muslim who had just finished Ramadan. They spoke respectfully of their own religions, their sacred texts, their spiritual practices. And yet, when discussing the beliefs of the ancient world, their tone shifted. The ancient Egyptians were gullible, easily manipulated, ruled by fear and convinced by stories. I was beyond curious that the possibility that the same dynamics might be present in the modern world didn’t seem to cross their minds.

Politics & Religion: The Unseen Thread

I found this both fascinating and deeply human. Full disclosure - I didn’t grow up with organized religion. My mom was raised Catholic, but left the church after years of wrestling with its contradictions. She kept her own quiet faith—intuitive, inclusive, and deeply personal—and passed that on to me and as a result, I’ve always felt spiritual, but never drawn to organized religion. I have no quarrel with faith—any faith—as long as it’s freely chosen, does no harm, and isn’t forced on others.

But walking through the remnants of temples where religion was explicitly designed in tandem with politics—where belief and obedience were part of the same structure—it’s hard not to notice the repetition. The guides spoke of the ancients as if their gods were obviously fabricated, their beliefs clearly constructed to maintain order and hierarchy. And yet, many of the systems we live under today seem startlingly similar. The costumes may have changed, the names may be different—but the scaffolding often remains.

This isn’t unique to Egypt. The entanglement of religion and rule is a global, cross-cultural phenomenon. In Rome, emperors declared themselves gods. In medieval Europe, kings ruled by “divine right,” with the Church not just blessing their authority, but often controlling it. Popes crowned monarchs and excommunicated their enemies. Religious leaders dictated what could be read, what could be believed, who could live, and who must be punished.

Even the English Bible—the King James Version—is itself a political artifact as well as religious. It was commissioned in 1604 by King James I of England, and was intended to create religious unity and reinforce the monarchy’s divine authority. The result was a beautiful literary text, but also a very calculated translation, carefully shaped to align faith with hierarchy and obedience.

Where religion and power align, wealth always follows. In ancient Egypt, temples owned land, levied taxes, and employed thousands. In medieval Europe, the Church amassed untold fortunes through indulgences and tithes. Today, megachurches bring in millions, often tax-exempt, while preaching prosperity as divine approval. Faith has long been a business—and often a profitable one.

A Violent History

The danger of unquestioned belief isn’t theoretical. Across history, some of our darkest chapters have been written in the name of gods.

The Crusades.

Human sacrifices of the Aztec, Mayans, Incans.

The Inquisition.

Colonial conquests and forced conversions.

The burning of so-called witches.

The justification of slavery through scripture.

Sectarian violence in Northern Ireland, India, the Middle East.

Suppression of women’s rights and honor killings.

Terrorist acts in the name of god(s).

Genocide.

Violence in the name of religion isn’t an ancient problem. It’s a modern one. It is not gone, it is simply better dressed. And so I sat with this question, quietly, as guide after guide explained how religion had been used in ancient times to manipulate the people. I didn’t ask it out loud—but I wanted to: Do you think we might be doing the same thing now? Why is it so easy to see the past, but not the present? Why are ancient myths labeled as tools of control, while modern ones are taken as sacred, unassailable truths?

The Retelling of History

Coptic Christianity did not arrive in Egypt through colonization or conquest. It was born there. According to tradition, Saint Mark brought Christianity to Alexandria between AD 42–62—more than three centuries before Christianity was legalized in the Roman Empire and long before it became Europe's dominant religion. For centuries, Egyptian Christians practiced their faith under persecution. They are among the oldest Christian communities on earth.

And yet, in much of the Western world, Christianity is still framed as a European religion. In Europe and the western world, we see how belief is reshaped to serve power, geography, and narrative. The depictions of Jesus where he has lighter hair and blue eyes are most likely historically false. Given his geographical location at the time he would have most likely been shorter and stockier in stature, dark haired, olive skinned and dark eyed. But time and power has white-washed him into someone the Europeans could relate to more.

This happens everywhere. From Vatican palaces to evangelical megachurches, from Islamic caliphates to Buddhist nationalist regimes, we see the same gray area in which those in power claim divine authority not to liberate, but to control. To turn faith into armor, into law, into leverage. Into something unchallengeable. And so I return often in my mind to those temples. The thick stone walls. The incense. The hidden chambers. The careful choreography of belief. And I think of the people—earnest, hopeful, frightened—who stood outside those chambers and believed the gods were speaking.

And I wonder: Are we so different?

A Closing Reflection

I’m writing this from Greece, where Holy Week fills the air with music, candlelight and rituals. In our small village, faith is everywhere—bells ringing, people fasting, services held each night. There’s undeniable beauty in it. A sense of rhythm, of community, of belonging. Religion, at its best, can be a container for meaning. A language for grief, for joy, for connection - and it’s easy to see that here. The Greek Orthodox church binds the community together and provides a framework for culture. Most religions, at their core, share similar values—compassion, humility, service, love.

I believe there is beauty in all things. I believe most people are inherently good. I believe most people share the same wishes and fears - they want to be safe, warm, loved and see their families thrive. But I think we must be mindful when beliefs are institutionalized and politicized, and the lens shifts. It can become us versus them, civilized versus heathen, saved versus lost. And that’s where I think we lose the thread.

I wish for all people the freedom to believe, to question, and to find comfort in what they hold sacred—without needing to prove it, weaponize it, or impose it. We owe that to each other and to all the gods, both old and new.